Tomas Ives: Painting for the People

Tomas Ives is a self-taught artist and designer devoted to creative communication through art, illustration, design and motion. Having grown up in a convulsive political environment where expression was synonymous with resistance, his work considers the conflicts and movements that inspire changes in people and their perceptions. His figurative landscapes are guided by surrealism to trace a message through Latin American patterns, and he finds great satisfaction in sharing his work with his people and contributing to a wider consciousness of their stories. Tomas has illustrated four books, won a couple of international awards, and once stirred up Chilean politics with his drawings!

Pictoplasma: Can you remember an initial moment for how you perceive yourself as an artist?

Tomas Ives: I grew up in a convulsive political environment, where expression was a synonym of resistance. One day, a boy from another neighbourhood threw a cassette on my head. When I put it on my radio, there were wonderful melodies, unheard by a child that grew up inside a dictatorship. Years later, I knew it was The Clash, and that's how punk got a hold of me.

I like to think of art and creation as a tool to improve people's lives. My compositions, despite coming from surrealism and being full of characters that live in our subconscious, are built through a very deep political reflection, I think.

You mostly work with a very reduced colour palette.

I use black because it's not a colour. It is achromatic – literally, a colour without a hue.

White, in opposition to black, symbolizes deep contrast or the dialectics. And crimson red is a colour that comes from the pigment extraction from the cochineal bug that you find here, in America. Seventy percent of the flags of the world use it because it symbolizes passion, blood or intensity.

I was kicked out of art school, but I’d learned screen-printing there, and it was my favourite method of image production. Almost all my projects start on paper, or even just scratches on the walls, but they always end up in the workshop. My art is always looking for masked characters, perhaps because masks give us that freedom to be who we really are or what we really want to be.

Can you talk more about your interest in masks and also the fact that a lot of your characters have animal heads?

When I was living in Germany and trying to learn a bit of German, I found this word – I don't know if it is a common word, it’s ‘Maskenfreiheit’ (freedom of the mask) – and I think it defines, in an excellent way, what it feels like when you wear a mask; you're actually you, you feel that kind of freedom, that liberation in wearing a mask and not being the you that is usually presented. Can you imagine, for example, if I wear a mask of myself and go to a party, disguised as myself? I would probably be an obscene, exaggerated version of myself because I'm not myself, but pretending to be myself. That’s what really excites me about masks.

Also, in South American culture and Andean culture, masks are really important in all the carnivals. When you see people at the carnival, they're always mascots – devils as bears, the young dressed up as old people, as angels, etcetera – and they dance. In South American culture, they represent all the things that are going on in the subconsciousness. So, I always try to use these characters in the first place because I love them. I develop the idea that they have their own personalities. The bird is about one thing, the dog is about another, and so forth. I love the idea of letting subconsciousness flow through the mask wearing characters, as a celebration of the ‘Maskenfreiheit’ culture.

You did a very controversial illustration for a performance of a band at Lollapalooza in Santiago 2019. What happened?

After the murder of a young man, Camilo Catrillanca, from the Mapuche nation, by the hands of the police, many of us were outraged. Also, the indifference of the right-wing government was even more outrageous. That is why I decided to use the faces of the Chilean ultra-right in an iconic image that symbolizes decolonization through the representation of the way in which the Spanish conquerors were killed in revenge by the First Nations.

I was playing with this logo and experimented with line drawings. What I tried to do was actually connect with the Chileans’ feelings of anger and frustration about what was going on in regards to these assassinations. I showed the drawings to the band, Fiscales, and we used them for some of the visuals for their concert at Lollapalooza. But we’re talking about a moment, you know? These visuals didn't take up the whole show. Destiny is really a funny thing, because at the same moment that the band was playing, the president of Chile was visiting Lollapalooza. That's probably why it became viral, because the guy said, “OK, wait, why is this happening? Ban this! Shut it down!”

Did you have any arguments with yourself about depicting brutality? How far do you think you can go, for instance? Do you have your limits?

I guess it depends on the context. I probably wouldn’t have done such a thing if it wasn't that band – Fiscales are a punk band – in that situation. In the 1980s, you could see similar images about Ronald Reagan in the US, or maybe Dadaism dealt with personalities like this back in the early 20th century. In my way of thinking, and with the movement that I joined as an adolescent, it was punk rock, made for people familiarised with these kinds of brutal images. It’s not a photo. It's not realistic. It's just a line drawing. When I was in school, you usually drew things that were a little bit violent or obscene, and it's a bit like that. How far can you go? It actually depends on the context, right? But I didn't want it to be something that defined my art or my creation from that point into the future, so that every time you google ‘Tomas Ives’, you find ‘the guy that did that’. I didn't want that.

These works reappeared again in yet another political context.

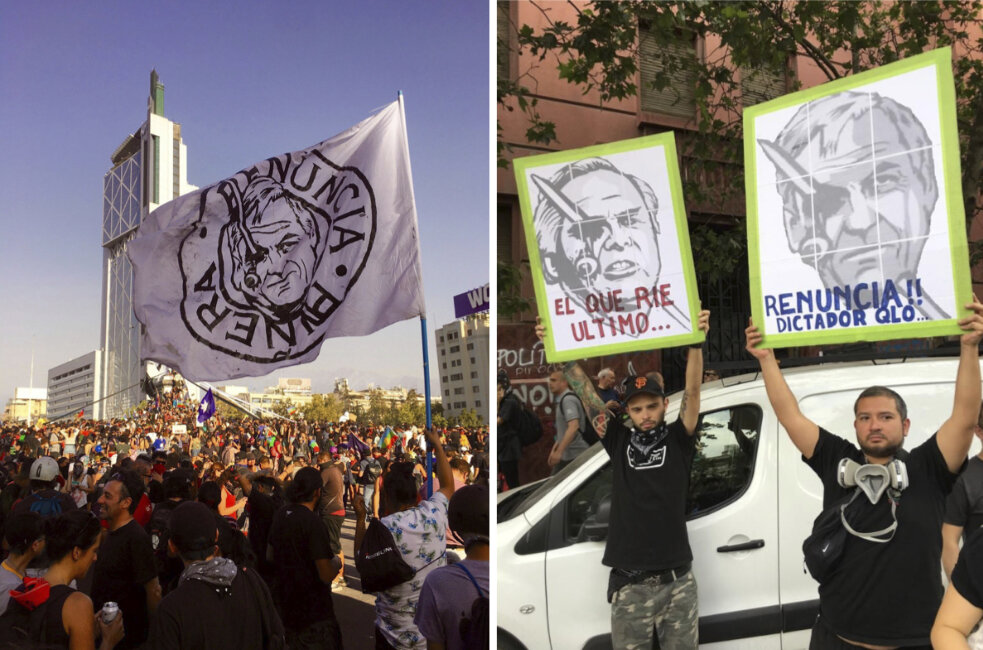

Yes, Lollapalooza was in April 2019, but the most shocking was yet to come. In October of that same year, a great social outbreak took over the streets of Chile. Discontent, anger and injustice led the people to demonstrate together in search of a new social pact. Unfortunately, I was away in Germany, but what happened in April fed into the flags of the fight in October. Finally, the images turned into wonderful slogans, which separately represent different periods, but all together represent a chain. They became anonymous, and therefore, public domain.

After this episode, many jobs were frustrated for me. One of my teachers, Mono Gonzalez, an old popular muralist in Chile, told me, 'You should paint more walls because the world is full of them.' I listened to him and started painting more and more walls. I like the idea that, when you paint in a neighbourhood, community or city, you're actually painting for all the people living inside of it. That is why I take time, because I think it is important to listen, talk and be sensitive to what it is that people value in their life and environment, so I can find convergence between the community and work.

“Masks give us that freedom to be who we really are or what we really want to be.“

You are currently involved in public arts for a Haitian settlement. Can you tell us about that?

During the coronavirus crisis in Chile, a predominantly Haitian settlement arose in the

south of the city. When I got there to work as a volunteer, I realised that there was no city planning, but more importantly, there were no tools to form a territorial identity that would

help the more than 2500 families that inhabited the settlement to have a sense of belonging to the sector. I started working, designing a map of the place. These types of settlements are illegal. Therefore, there were no technical advisors from the government. Today, after one year of field work, we have managed to develop a complete map of the site. Thanks to this, the inhabitants have given it a name and an identity: The Condors of Lo Errazuriz. And we are preparing a community visual identity.

How come the condor is the starting point? And how did you develop this identity so that the people who live there actually identify with it? Can you tell us a bit about this process?

As I mentioned, I started by drawing a map, because there was no map, and there weren’t many pictures and satellite images on Google Maps from which I could start drawing a map. I started with drones, taking photos, and I realised that the roads inside this settlement have the shape of a condor. So, I thought I’d propose that, and this is really funny because we live in a city surrounded by the Andes Mountains. If you climb up a mountain, you will find condors up there. The symbol for all the Andean cultures is the condor. It was a funny coincidence that the roads appear like a condor, which turned out to be part of the settlement’s identity.

“You should paint more walls because the world is full of them.“

Who finances these buildings in the Haitian settlement? And who finances the infrastructure?

There's no institution or government involved in it. It's all made by the people themselves, they finance this. There's no intervention from any institution, it’s the people's work.

Have you contributed any further art work to the settlement apart from the map and the identity? If so, is that in some way financed?

In regards to financing, I'm the financer. I do jobs so that I can afford to work there as a volunteer. It's a huge settlement. Recently, I heard that it is the largest human settlement in South America. There's a lot of people living there. It's actually like a city. There are different sectors, and each sector has their own representative. We gather together every week or so, and of course, issues come up. We try to focus on what kind of solutions we can create, or the communication we need to help inform the community or start a campaign.

I try to get into it, proposing ideas. I try to work on stuff with them. For example, they recently created a space that is like a square, with play spaces for kids to play and smoke and play football. They asked me to do murals all around it, so I started a conversation and making some proposals. Basically, it's just like working with a client, but in the capacity of a volunteer.

How did the conversations influence the mural and shape the motifs you would choose?

Usually, as a methodology, I try to gather words and ideas from the people, just simple words such as, for example, migration, dignity, fraternity, gains, etc. Then I start composing with representations of each and every concept, word or object inside a whole composition.

I try to frame it in the context of my work as an artist. I go to them with a digital proposal, and I ask for feedback and start moving. It's really slow in the sense that there are usually a lot of conversations. As soon as you propose something, new ideas pop up. When people see something visual, they realise, OK, we can do something. New ideas start to pop up as you work together. I know some things will change along the way, so you have to be patient.

It must be an interesting process, because you actually have the people who you talk to watching what you're doing while you're doing it, giving constant feedback.

Exactly. It's just like that. You have an ongoing conversation between words and drawings and painting.

Interview by Pictoplasma published in Pictoplasma Magazin – Issue 2: Character Care, 2022