Felix Colgrave: Animation Is Sensory

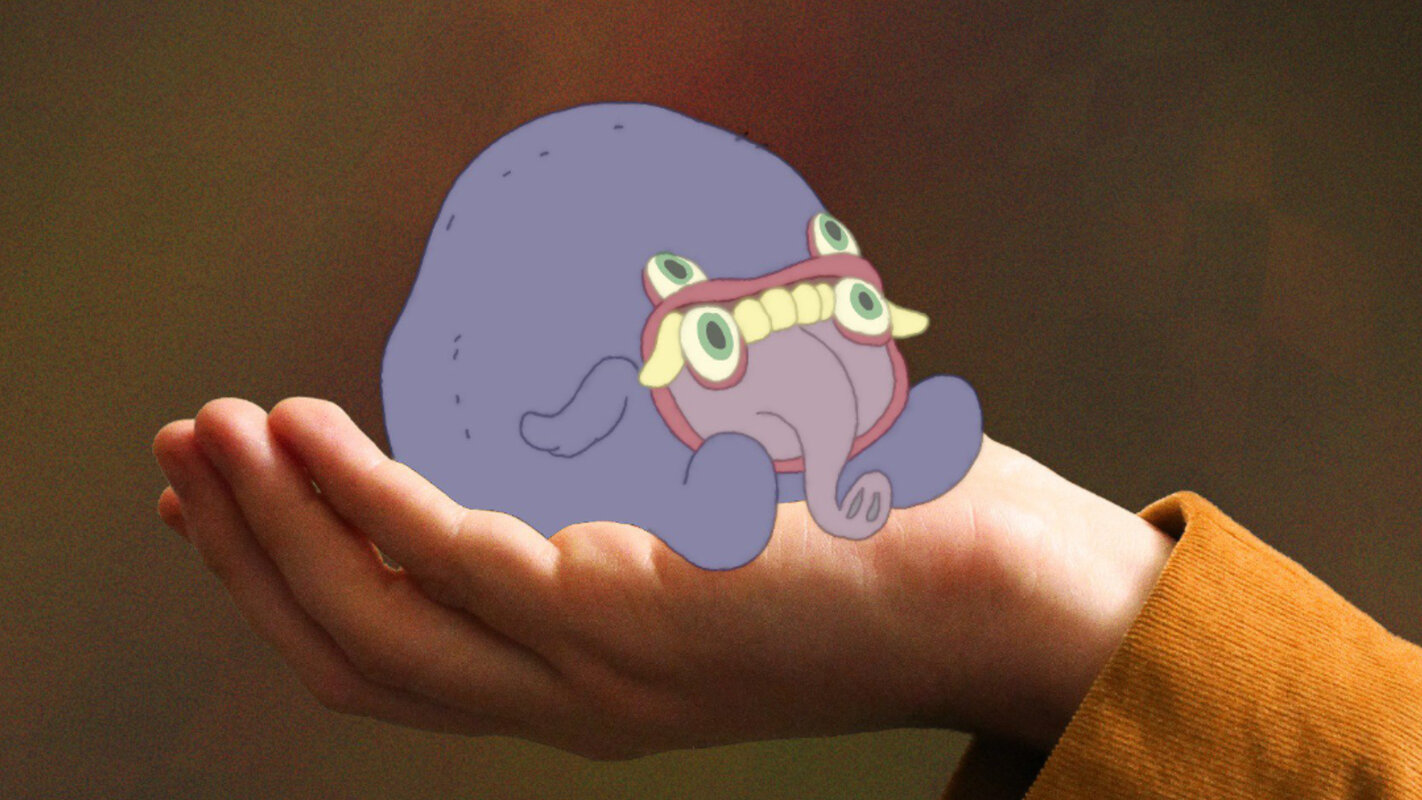

Raised by former hot-air balloonists in the countryside of Tasmania, Felix Colgrave taught himself animation as a child and has been publishing independent short films online since the age of 13. He studied animation at RMIT University in Melbourne, with his graduation film The Elephant's Garden winning Best Australian Film at the Melbourne International Animation Festival. His films have amassed a dedicated global following, with over 170 million views on YouTube and countless more on other platforms.

Pictoplasma: Can you talk about your approach to animation?

Felix Colgrave: I don't want to make a TV show where there's one department of people doing all the making and another department having all the ideas. I love being able to sit down and make something by myself, the way an author can sit down and write a book or a painter can do a painting by themselves.

“There's a lot of facets to animation, and any one of them can be in control.“

How is that possible? Don’t you need a plan before you do the actual animation?

There are so many ideas that can only develop if you have an immediate relationship with your medium, if you're directly interacting with it. Sure, you can write an animation. You can also animate an animation. There is this irritatingly pervasive idea in film that writing is where all the conceptual weight lies, all the ideas and meaning, while what you see – animation and actors, cinematography and set design – is just the practical stuff that serves the writing.

I don't need to mimic an industrial pipeline and split my labour into imaginary departments. There's a lot of facets to animation, and any one of them can be in control. If I start by drawing or animating or playing music, all the creative decision-making usually determined by writing doesn't just evaporate, it comes through the task that's leading the dance. Often, I start a scene with an idea pertaining to motion, and I try to invent a technique to make it happen. Maybe it won't come out how I’d imagined, but that's experimentation, which is fine! And then the narrative element, which we usually think of as belonging at the top of the idea hierarchy, is developed to give context to what you're seeing.

“Animation is the art of moments, and each moment is its own very carefully made thing.“

But what about the overall story line for a film? Don’t you have an idea for the narrative arc?

I like working without a plan, and I'll make a shot in its entirety before I start the next one. I’ll often do the whole film like that, in chronological order. I can completely finish the animation, the colours, the background, sometimes even the music for a full second shot before I've done even a rough sketch of the next shot. Sometimes, I might not even have an idea in my head for what happens next, but animation is pretty slow, so I've usually thought of something by the end of it.

Animation, especially animation without dialogue, is a sensory way of communicating a story, and I find it easier to have all of that sensory information present before I lock in what's going to happen next.

I like to leave opportunities to experiment and try out different techniques and let the medium take over a bit. Maybe it will come out quite differently to how I might have guessed when going into it. I think that's really exciting. If I'd already laid the groundwork for the next shot, storyboards and animatics and scripts, then that could cause some problems, because it might no longer match up. Even if I thought I had a really clear idea in my head of what I wanted to happen next, if I leave it open, last-minute changes don't create any extra work. They're not changes. It just keeps things fresh and spontaneous, as spontaneous as animation can be, even though it's all quite contrived by design. That doesn't mean the whole story is compromised either. It might just mean I decide I'm having fun with a little side character and I'd like to spend some more time with them before I go back to the main story.

In this way, you can make something a lot richer, and it's a lot less boring for you than writing something in one week and boarding it the next, and then spending two years animating it because then you've cashed in all your creative control at the beginning. Animation is the art of moments, and each moment is its own very carefully made thing.

That sounds very experimental. How do you still manage to tell your stories? Your films still feel narrative-driven in a refreshing and inspiring way!

People have often said that my films can't actually be about anything, right? They must be meaningless. We use metaphors to explain relationships between things by exchanging the tangible elements they connect. We swap out the nouns. We use cryptic metaphors for real world problems. But when I make a film about frogs and decide to draw frogs all day, it's because I'm sincerely interested in frogs. I think the way I tend to approach animals is that … they are animals, and I'm really interested in that.

“The internet is nice in that it's levelled the playing field. Anyone can tell a story that's really theirs“

You put all your films on YouTube and you have 1.5 million followers. Double King, according to YouTube, has been viewed 57 million times. How does that affect your work and the process of how you work?

It made me realise that the internet is massively beneficial as a distribution system when you work without dialogue. Something can catch on anywhere. It did make it a little intimidating doing something like Throat Notes, where the setting and the context was so specific to such a small part of the world. But that was balanced by the lack of dialogue. All over the world, we've all grown up watching American TV shows where they've never had to think about a reference to a specific supermarket, say, or all these things that feed through to an international audience. We all watch, and we all just fill in the pieces. If someone is making something for an American audience, they can get scared about what references they can put into the work. But I feel as though the internet is nice in that it's levelled that playing field. Anyone can tell a story that's really theirs.

So, you feel as though you have a direct line of communication to your audience?

There are no producers or anyone in the way saying, “Oh, people won't understand that reference.” I've watched plenty of things on TV that I haven't understood but I've still enjoyed. If I feel as though I'm missing context, I'll go and look it up. It is something that was only going to happen in the internet age, so I think it it's an opportunity.

How does this freedom in doing your own work and releasing it on the internet influence your commercial work? Do clients know what they’re getting when they commission you?

Regarding commercial work, I've definitely been approached by people that just want something that looks like one of my videos. They need particular technical skills, but then, who am I giving my brand to? And then, I've had client work where I've said I'm happy to do some drawings, but I don't want to make a direct link to my personal practice, can I draw for them in a different way? They usually say no. But overall, I've sort of taken a step away from commercial work in the last year or so, and that's been a big relief.

Interview by Pictoplasma published in Pictoplasma Magazin – Issue 2: Character Care, 2022

- 848 views

- 12x empathizes