EDUARDO NAVAS: CHARACTER CUT, COPY AND PASTE

Eduardo Navas is the author of the book Remix Theory: The Aesthetics of Sampling (New York, Springer Wien, 2012), an analysis of remix in art, music and new media. He received his Ph.D. from the University of California, San Diego’s Program of Art History, Theory and Criticism. From 2010 to 2012 he was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Information Science and Media Studies of the University of Bergen, Norway, where he remains an affiliated researcher. He currently researches and teaches Remix Studies and Principles of Cultural Analytics at Pennsylvania State University’s School of Visual Arts.

We asked Eduardo Navas questions on how remix functions in art practice – character design specifically – and if there is a difference between remix and sampling, among other issues that the concept of remixing raises with digital and non-digital forms of production.

Pictoplasma: Remix is what we all do now: cut, copy and paste. You have defined remix culture as the creative exchange of information made possible by digital technologies. Can one only speak of remix in cultural production if it is digital? Or, if the digital is not a prerequisite, how are analogue remixes embedded into digital culture? What is the difference between remixing and quoting or referencing?

Eduardo Navas: First, it should be noted that the concept of remixing is specific to contemporary times. Not everything is a remix. This is hard for me to say given that I was a DJ for almost fifteen years. I would love to make such an overreaching claim, but it’s precisely because I DJ’ed for so long that I know that remixing is a very specific act. Having said that, the principles of remixing—or remix as discourse—have become important across this culture. Remix culture is very popular today, especially when discussing creativity as endorsed by Creative Commons. A look back in history verifies that, as a concept for daily creativity, remix was not very popular until remixing became a driving force in music, particularly in disco and hip-hop. In other words, the concept of remix is popular today not because anyone in particular decided to talk about it in order to promote some sort of organized movement, but rather because culture as a whole began to use the term to describe the type of creative production that is possible with contemporary technology. The reality is that remix is synonymous with the digital process because it was this process that made it possible to take actual samples from recordings and manipulate them into something new, while leaving the sampled source intact. This was not the case with collages, which were created by cutting out from images or photographs to create new compositions. In collages, the sampled material was destroyed when it was cut out, but with digital technology, the sampled source is left intact. This has been done before in photography, of course, starting in the 19th century. When you take a photograph you are sampling from real life, but the subject of your photograph remains untouched. People at that time didn’t think about this as an act of sampling, but of recording. Nevertheless, early photography was, in fact, sampling from real life. In practical terms, quoting, if you reproduce the exact sentences, is the same action that takes place in music when one samples. Only the context under which it is done is different. A quote is generally used to prove a point in an argument, while a sample in music is used as a creative exercise, but they both use a basic principle of remix as a form of discourse. Although a quotation is not necessarily a remix, it could be if an artist deliberately disrupts the basic function of a quotation to make it a creative, artistic act. Referencing falls under the general paradigm of intertextuality, the embedding or citation of ideas within a text or a material form such as a painting, film, photography, multimedia, etc. There are many ways in which references or footnotes can open allusions when used in creatively within a text or an image. Yet, this is not necessarily remixing either, though in recent times it increasingly finds itself intertwined with remixing because of the way technology encourages the blurring of lines in creativity.

As curators, we have followed a quasi-structuralist approach, identifying the pop cultural iconography of character design and commercial mascots as a common denominator and language, and seeing remix as a manipulation of signifiers. Rather than claiming originality, artists embrace the visual white noise that surrounds them and, by changing small details, introduce a new message. How can you relate to this idea?

One misinterpretation when analysing remix beyond music is the idea that, somehow, such research kills “originality”. What becomes obvious is that our creativity has always consisted of making things that offer a unique vision based on an in-depth understanding of previously produced material. If you consider any novelist, any artist or any musician and you listen to how they speak about their creative process, they have all closely studied their predecessors in order to master the medium and its ideas. They can then recombine references and sources of their choice into something that is different from what was created in the past. This recombination of material and conceptual elements of sorts is so complex that, before we understood how we functioned creatively, as we do now thanks to remix studies as an actual field of research, we looked at creative production and called an author or artist a “genius”. Now the days of the genius are gone and what we currently have is a much richer moment where we understand that we are all connected and that we are able to contribute something unique because we have a much better understanding of the creative process. On the other hand, to begin thinking about changing little details in order to introduce a new message is quite deceptive in terms of creativity. Such a simple act could be artistic and creative, but it will unlikely be a long-standing work of art unless such simplicity is problematized to show how even its apparent straightforwardness can be appropriated conceptually to show the contradictions of originality and non-originality. To do this, one must understand the argument I’m making here about our creative process as an act of communication.

"There is no outside. Once we enter the symbolic world there is no getting out again"

Just as before, we realised that principles of remix inform all areas of communication and creativity. We need to keep in mind that we can always come up with something new that is unprecedented. Such outcomes can only happen, however, when we have a deep understanding and knowledge, not only of our history, but also of our creative process; all art from the past lives up to this test. Understanding the principles of remix can only help a creative person become a more creative individual. One cannot think, however, that we are merely cutting out little details here and there. Real changes happen when we make our own what others produced in the past. If originality still exists today, this is the only way that it can come about.

We live in times of non-stop image production and consumption. TV, newspapers and billboard advertising have been overtaken by an endless interaction with the glowing surfaces of our digital devices. Is remix the only way to cope with this visual stream now that there is no image outside the box? Is it the fate of our digital culture?

Eduardo Navas: There is no outside. Once we enter the symbolic world there is no getting out again, unless we lose self-awareness or die. One could somehow get off the grid, severing contact with all media and cultures but, even then, if this rather romantic and delusional decision is made after growing up with the concepts of our current global culture—which in a large part is an extension of Western culture—even then, if you decide to become a hermit, you will negotiate your existence in some context based on those Western principles. From this stance, to think of being outside the media—or outside the text, for that matter—is a mute argument with a dead-end. If we think of remix as a discourse, I would say that remix principles as we understand them today are the only way to deal with the visual stream that you mentioned. Now, this does not mean that everything is a remix. It just means that things are composed of other things. If you want to be reductive, then a more realistic statement would be that everything consists of samples, citations or reinterpretations; however, such elements don\’t necessarily add up to a remix, but are rather an object or a piece dependent on remix principles. For example, Chic’s song Good Times was sampled by The Sugarhill Gang for Rapper’s Delight, but the latter is not a remix; it only uses a sample of the former song in order for rappers to improvise their rhymes and create a new recording.

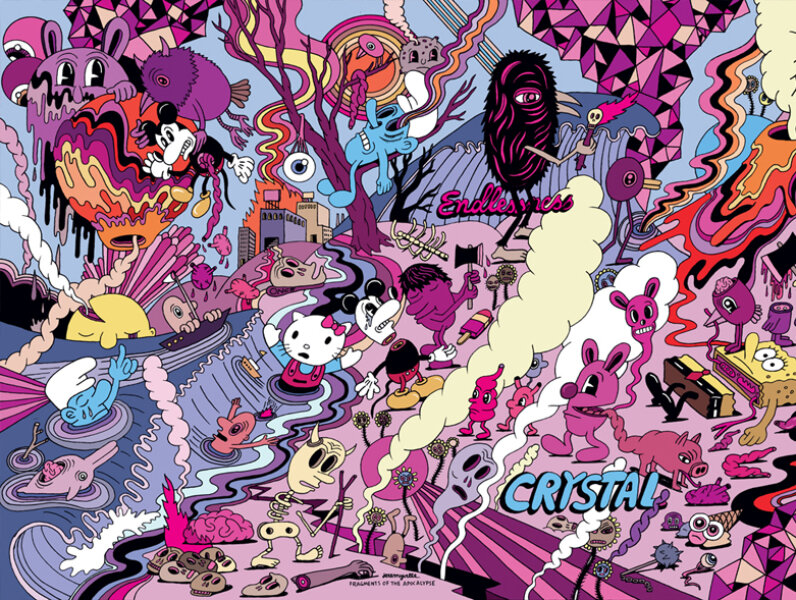

How could one identify different remix strategies using examples from the White Noise exhibition?

Ian Stevenson’s painting Do You Want Fries with That (top image)… uses the Ronald McDonald character in a deformed silhouette. This is what I define as a cultural citation, meaning that the form is not a concrete sample, but a reference to another form that one is likely to recognize as pre-existing because of a shared culture. It is not a reference, but rather an illustration of something—in this case Ronald McDonald. What is taking place here is more along the lines of a cover song performed by a band. In such a case, one evaluates the image based on its likeness to the reference, on how similar and different the “cover” may be. It’s just like a cover recording or a performance: one may actually like it more than the reference, or just say that it\’s different, or that both are quite interesting. Kurt Separately’s Radiant Face Projecting Beauty Anime Girl works directly with the source material, deconstructing an iconic manga character into a dysfunctional glitch. This is a remix defined by material sampling, meaning that the actual sampled material is manipulated to develop a unique composition that may still make reference to the sampled source.

Originally published in the “White Noise” catalogue accompanying the Pictoplasma exhibition at La Casa Encendida, Madrid, 2013

- 167 views

- 0x empathizes