Baphoboy: Land of Smiles

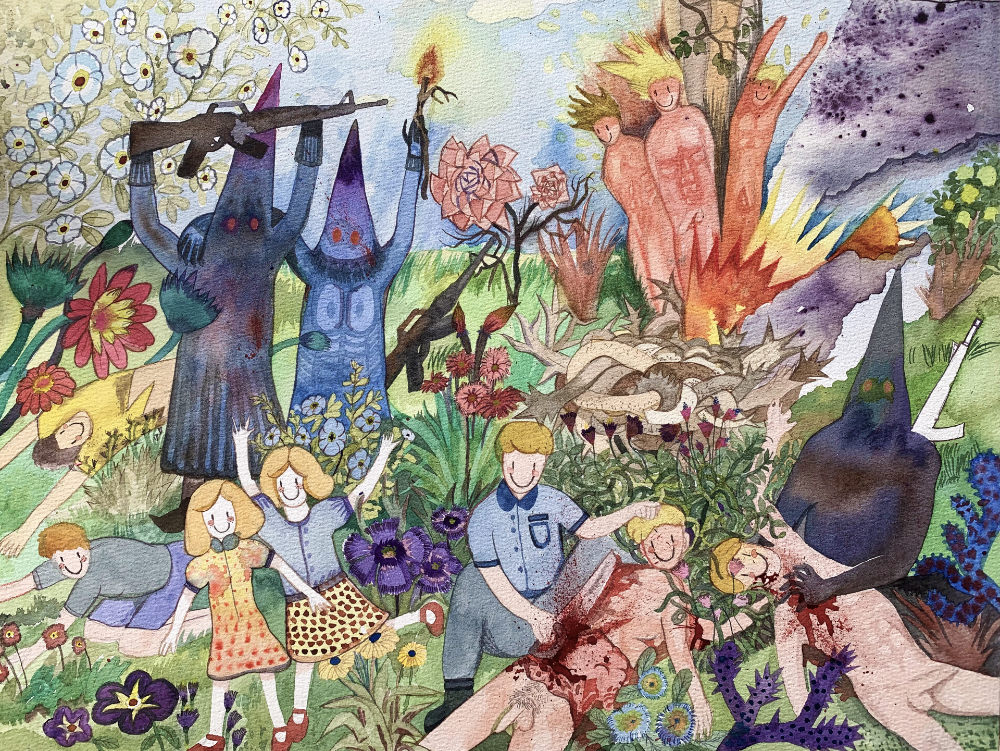

Baphoboy is a political artist based in Bangkok. With his characters, who are often fixedly ‘smiling’ and engaged in sexualized, ultra-violent imagery, he holds a mirror up to Thailand’s elite, and hopes to draw a wider audience to politics and encourage them to care about basic human rights, equality and fairness in Thai society. Baphoboy’s work usually contains hidden messages and symbols: The more you know about Thailand and Thai history, the more you can see in the images.

Pictoplasma: Where does the name Baphoboy come from, and why do you use a smiling face?

Baphoboy: Baphoboy is actually a character that is a manifestation of Satan. When I was young, I was one of those kids who thought differently. I was also called deviant. When people think of Baphoboy, they think of a smiling face, and I use smiling faces in my art to communicate a message. I play with the ‘smile’ in the context of Thailand’s nickname, ‘The Land of Smiles’, or ‘Yim Siam’ in the Thai language. It’s a discourse that is trapped within the social structure. It seems as though Thai people are happy, whatever happens, but that’s how we’re represented to foreigners, to make them feel that Thai people are happy. Thailand, seen through foreign eyes, is a land of milk and honey. Thai people love to pay respect and smile, but from outside, you never know what happens in this country. This is what I’m trying to represent in my artwork. People are not smiling because they are happy, but because they have learned to accept the fact that they are treated badly. Smile stands for injustice. Smile stands for violence.

“People are not smiling because they are happy”

Can you say something about your creative process?

I mainly get inspiration from the news. I use the negativity to create art. Therefore, my work has to be up to date with the current situation. Right now, the news from Thailand, and on a global scale, is thrilling and stirring, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. After I watch the news, I draw the cartoons in software called Clip Studio. After that, I use Photoshop to edit the colour. I often have many shortcuts for creating my work. For example, I use collage, I copy photos, I duplicate a character.

I usually post my work on social media to create an impact on society. I would like to make a difference, not just make works for people to appreciate the beauty. I post something for society, to provoke something. Therefore, most of my art is created from social media to be posted on social media, in order to make a huge impact on social media.

“When I was young, I was one of those kids who thought differently”

How would you describe the current situation in Thailand?

We know that something is blocking the truth. The situation is bad and getting worse. It’s a tragedy. In my point of view, this country is still an underdeveloped country. People are still taken with the propaganda of the government and military, and Thailand still has a monarchy, which is the parasite system that stops society moving forward. A lot of people get trapped in the propaganda and believe that people are not equal, while in many western societies, people see equality as normality, and can discuss things. In Thailand, I cannot overcome this obstacle against talking about gender equality, but I have to try and make it apparent.

What you do is quite political. Are you safe in Thailand?

I find it really strange, as I know many artists who have done political work and have faced criminalisation and been arrested. But I have been doing this for three years and nothing especially serious has actually happened to me. I haven’t prepared for how I should deal with the political consequences. It’s a strange case indeed.

If you are quite famous on Instagram and the internet, is this also some sort of protection? You are too well known for something to happen to you?

From my experience, having many followers might or might not help. It is no guarantee. In my case especially, it is actually very hard to pinpoint what you can criminalise in my work. I operate in a grey area. And it’s also a government strategy to wait and decide which artist or activist they want to arrest. We have a saying; you slaughter a chicken in front of the monkey and the monkey gets scared. That is the practice of the authorities. They wait and see if it’s worth arresting me.

“My work talks about social hierarchies”

You not only depict politicians and the military, but also doctors and nurses. What is that about?

My work talks about social hierarchies. The military belongs to one hierarchy, the doctors and nurses belong to another hierarchy, and the children to yet another hierarchy. A lot of pieces are made at the time in which things are actually happening, in real time, so, they’re a depiction of reality.

Did you make this kind of art before your time in the military?

Before military conscription, I was studying fine art at university. I was conscripted into the military at the end of my studies, and when I came out of it, the protests and harsh reaction of the military were in full swing.

“In Thailand, I cannot overcome this obstacle against talking about gender equality, but I have to try”

Can you explain why you use aggressive metaphoric visual language?

We have to clarify why it is necessary. My country is not safe. Something is threatening us, which is the law of the country. There are so many limitations in terms of speaking up. One time, my work was deemed criminal. Art is something that you should discuss or criticise, it should be like that. Visual art is a common language. That’s why we can use it to call out to the world, to let everyone know what is happening in Thailand right now. I feel that my art is about explaining and disclosing something that cannot be spoken. If you are in Europe, you can talk about whatever you want. You could criticise any topic. Unfortunately, that is not so in Thailand, even if it is better in some other Asian countries. My art seems violent and aggressive, but actually, there is no violence of any kind. But for half of the people who handle or wield the power of the constitution, my art is a crime. I’ve been threatened in many ways. I’ve had unrelated works that were spammed, and I’ve been intimidated. Not physically but verbally, in the comments on social media. There is a system called I. O. that is doing it. I even used to be a part of that.

How so?

The military system in Thailand is a servant system. I was one of them, a servant. I used to be a soldier under that system for about six months. Therefore, I know how they work. The system is formed to attack those who are against the government. It’s simply called I.O. My work criticises the government, therefore I was attacked aggressively by I.O. on social media. They assaulted, swore and cursed harshly, in unintellectual ways. The obstruction and intimidation from the government is completely targeted on artists who are against the government, against the elite in Thailand. These artists are having a hard time in these circumstances.

You also have another group of works in which you depict fields of flowers. Tell us about these.

I often tell a tragedy through a field of flowers. I use cartoons to tell violent stories. I use a rainbow to represent blood. Actually, it is the same meaning of the ‘smile’ that I interpret in these images: Thai smiles that hide all the pain and sadness. All you can do is smile. I’m telling you about the bullets, but I can’t do it directly.

You also talk a lot about gender and sexuality in your work.

Previously I held an exhibition called NOBRA, talking about LGBT issues in order to normalise them. I talk about this topic not only in this exhibition, it is implied in every one of my artworks. Whether I criticise the military or criticise the government, LGBT stories are embedded in the works. It may be about gays in the barracks, or the expression of femininity and masculinity. There will soon be an exhibition about being a soldier, as I have lived in barracks and know about that life. Thailand still has conscription, even though we are not in any war. They still force male youths who are about to graduate or living their life to join and end up in the barracks.

“I often tell a tragedy through a field of flowers”

Do you feel you are part of a movement? Are you linked to any other artists in Thailand?

Yes, many Thai artists have gathered together for exhibitions to indicate that we won’t yield to the power. My works have always been part of these exhibitions, but I have not yet had a solo exhibition. I am still a young artist.

In the LGBT exhibition, NOBRA, I criticised the social structural problems, rather than focusing on myself. In Thailand, people use religion as a tool to oppress sexual and gender diversity and oppress humanity. So, in the exhibition I talk about gender inequality through a religious lens. I apply Buddhism into a story that tells why we, as LGBT people, are discriminated against. Is it you? Or your parents? Or actually, is it religion and the social norm saying that we are weird and deviant? It was intriguing to imagine an artist who would be bold enough to portray Buddha telling people that he is guilty for causing discrimination against LGBT.

I’m just a young boy trying to fight back a huge power. I want to be an inspiration to other people who dare to question the power that we are facing. If I can do it, I think the other 60 million people in this country will be able to as well. That’s the function of my art.

Interview by Pictoplasma published in Pictoplasma Magazin – Issue 2: Character Care, 2022